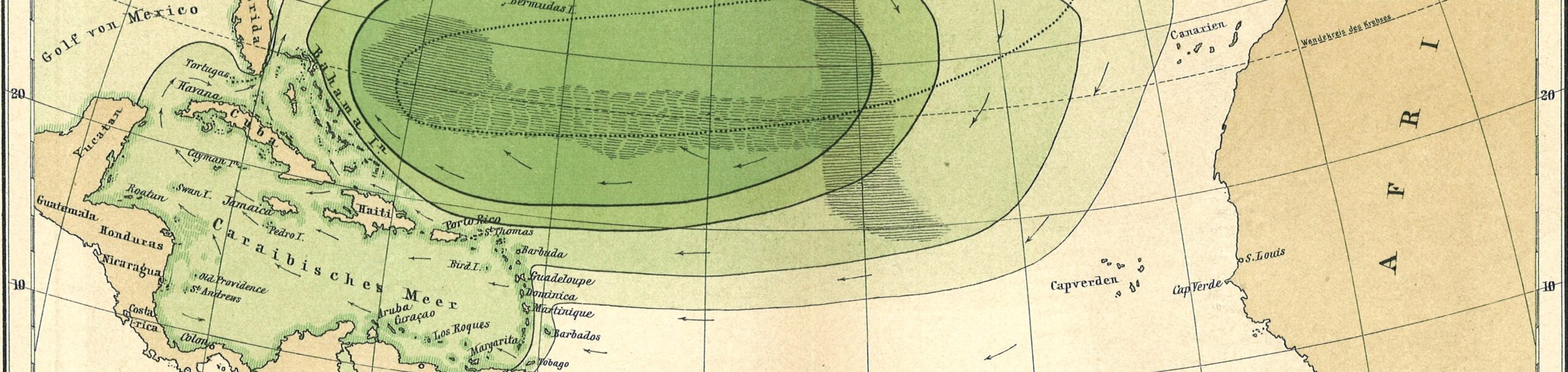

Selection from: The Sargasso Sea by Professor Otto Krummel. In: Petermann’s Geographische Mitteilungen 1891. Graphic 10. Voyage To Inner Space – Exploring the Seas With NOAA Collection Credit: NOAA Central Library Historical Collections. CC BY 2.0

Getting Started with QGIS

QGIS is a sprawling, massive, powerful piece of software. We spoke briefly last week about QGIS, its ethos and principles, and what it means to have software this capable and flexible available for use around the world. Now, we will begin to see some of the many things we can do with QGIS.

The activity for this class is available here:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/10vQWbJFeuFvA0VT2Fnb6uMgJaBF1aL7jIPag6py1ngM/edit?usp=sharing

We will continue to use QGIS throughout the remainder of this course. For now, we will bring in downloaded layers and connect to Web Mapping Servers to display layers managed by remote entities like the Pennsylvania Spatial Data Access clearinghouse (PASDA), Montgomery County, PA Mapping and Data Services Division, Google, and OpenStreetMap.

We will also learn some basics to navigate the QGIS graphical user interface (or GUI), and how to save a QGIS project.

[Bonus] A Case Study

OpenStreetMap

For hundreds of years and more, cartography and maps have been a fundamental tool for colonizers. The assumed right to (re)name places and to draw boundaries upon maps provides an occupier amazing powers to justify territorial claims and to literally erase what is contrary to those claims.

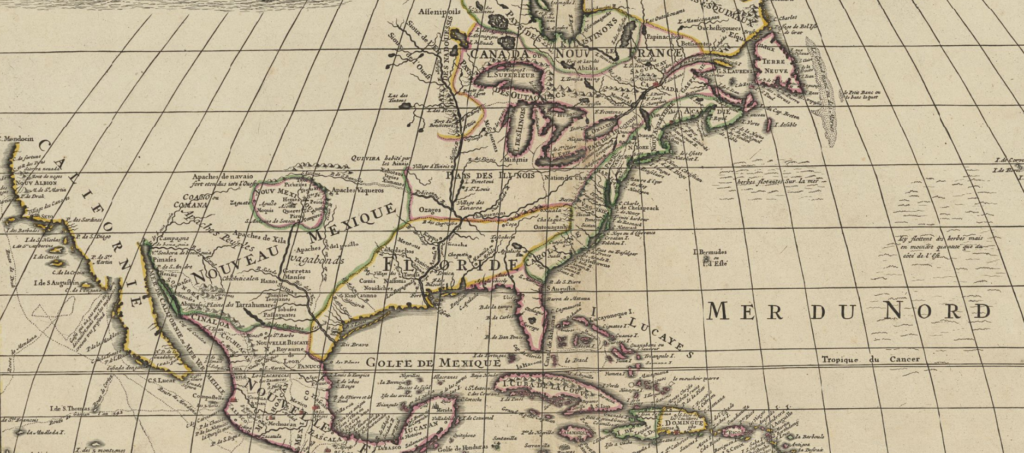

Consider this selection from a 1739 map of North, Central, and South America in Muhlenberg’s Ray R. Brennan Map Collection (you can see the full map by clicking on the link in the citation below).

L’Isle, Guillaume de, 1675-1726. L’Amerique Septentionale. Map; Image/TIF, [1739]. JSTOR, https://jstor.org/stable/community.20185533.

In the 21st Century across North America and elsewhere, we are reconsidering our colonial legacies, notions of ‘manifest destiny,’ and how these and others aspects of our past shape our landscapes and our perceptions of the places we know.

Consider President Barack Obama’s and Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell’s 2016 order to rename North America’s highest peak (formerly Mt. McKinley), Denali, which derives from the Koyukon language, spoken by native people who live to the north of the mountain.

The power to name, to demarcate, to declare through maps — is a tremendous power. OpenStreetMap is one effort to reclaim this power by those who live locally and know best about the places being mapped. Like other crowdsourced open projects (for example, Wikipedia), OpenStreetMap is community driven, openly licensed, and draws on local expertise and editorial supervision. Unlike most maps and atlases, the history of revisions is visible for all to review, as are the debates among members of the OpenStreetMap community.

Historically, the cost of maps has been a major impediment to their use by local people in parts of the world made and kept poor through colonialism. OpenStreetMap is free to use AND openly licensed, thereby facilitating reuse and adaptation by others without the need to seek permission. Rather than erasing contested geographies, OpenStreetMap offers the promise of greater and more equitable participation. Its web-based, born-digital nature introduces technological capacity for visualizing contested places differently than static mapping, and invites more egalitarian engagement in the production of maps that privilege local expertise and perspectives.

Learn more about and explore OpenStreetMap here: https://www.openstreetmap.org/